John Porter from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (London, United Kingdom) recently argued that in order to make sure “the disease does not go underground”, the “elimination” strategy must be swiftly converted to a “post-elimination” strategy.

John Porter from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (London, United Kingdom) recently argued that in order to make sure “the disease does not go underground”, the “elimination” strategy must be swiftly converted to a “post-elimination” strategy.As recommended by many leprosy experts, this post-elimination strategy should focus on integrating leprosy control activities into primary health care services, assuring early case detection, adequate chemotherapy, prevention of disability for all patients with nerve damage, and physical rehabilitation of those already disabled.

Work to dispel the stigma of leprosy and to introduce patients back into their communities must also be strengthened, experts note, in order to end social discrimination toward people with leprosy. Leprosy remains a disease of the poor, although the exact social factors that put people at risk have not been identified. To break this link between leprosy and poverty, “leprosy should…now be included in the portfolio of diseases associated with poverty, and leprosy work incorporated into poverty reduction programmes,” points out Diana Lockwood of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine .

Lockwood and Suneetha have also suggested that the routine use of vaccination could benefit the outcome of WHO's anti-leprosy strategy. Although the development of a specific and highly effective vaccine against leprosy is not yet a reality, the tuberculosis vaccine bacillus Calmette-Guérin, made with live attenuated Mycobacterium bovis with the eventual addition of heat-killed M. leprae, has been proven to offer some immunity to leprosy. Its reported efficacy ranges from 34% to 80% in different countries . Despite this variable efficacy, bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination is already widely used in leprosy-endemic countries—but who should be vaccinated, when, and how often in order to achieve maximal protection among the population are all a matter for debate. Another promising intervention for leprosy prevention comes from a recent study, conducted on five Indonesian islands, that found that giving people who are in close contact with patients with leprosy a short course of rifampicin can reduce their risk of developing the disease.

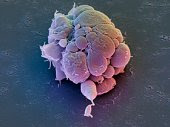

Finally, important research issues remain to be addressed. They include developing improved diagnostic tests and better ways to monitor and treat nerve damage, and understanding why MDT has not interrupted transmission. “We shall not be able to eliminate leprosy until we have a better understanding of its natural reservoir,” says Donoghue. “There are several interesting reports that indicate that there may be an environmental reservoir for M. leprae—perhaps even in the soil in endemic regions.” Healthy human carriers also do exist, says Donoghue, who points out that by using sensitive molecular methods it is possible to detect the DNA from M. leprae in people who showed non-specific skin lesions and who had not been thought to have leprosy. Even after a ten-year MDT programme, more than 5% of healthy individuals in a leprosy-endemic area were positive for M. leprae DNA in their nasal passages, a recent study found, suggesting a high level of environmental contamination. “Before anyone can talk about eliminating the disease we have to understand where the organisms are found, and the circumstances that result in an active infection,” Donoghue says.

Finally, important research issues remain to be addressed. They include developing improved diagnostic tests and better ways to monitor and treat nerve damage, and understanding why MDT has not interrupted transmission. “We shall not be able to eliminate leprosy until we have a better understanding of its natural reservoir,” says Donoghue. “There are several interesting reports that indicate that there may be an environmental reservoir for M. leprae—perhaps even in the soil in endemic regions.” Healthy human carriers also do exist, says Donoghue, who points out that by using sensitive molecular methods it is possible to detect the DNA from M. leprae in people who showed non-specific skin lesions and who had not been thought to have leprosy. Even after a ten-year MDT programme, more than 5% of healthy individuals in a leprosy-endemic area were positive for M. leprae DNA in their nasal passages, a recent study found, suggesting a high level of environmental contamination. “Before anyone can talk about eliminating the disease we have to understand where the organisms are found, and the circumstances that result in an active infection,” Donoghue says.