welcome to the science live world

Here you get the cutting edge knowledge about science and biotechnology impacts

and their solutions.

look out the next pages to ENTER out world...............................

DNA | protein | aminoacids RNA gene genomics proteomics trancription nanotechnology trna mrna rrna enzymes cabohydrates polypeptides chromosomes bioinformatics diseases microbiology biochemistry environmental sceince

testifies of the love another person has for the leprosy-affected. Instead of pushing the leprosy patient aside, the bandage-makers make a personal sacrifice of time to serve them. This is the greatest value of the bandages!"

testifies of the love another person has for the leprosy-affected. Instead of pushing the leprosy patient aside, the bandage-makers make a personal sacrifice of time to serve them. This is the greatest value of the bandages!"  John Porter from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (London, United Kingdom) recently argued that in order to make sure “the disease does not go underground”, the “elimination” strategy must be swiftly converted to a “post-elimination” strategy.

John Porter from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (London, United Kingdom) recently argued that in order to make sure “the disease does not go underground”, the “elimination” strategy must be swiftly converted to a “post-elimination” strategy. Finally, important research issues remain to be addressed. They include developing improved diagnostic tests and better ways to monitor and treat nerve damage, and understanding why MDT has not interrupted transmission. “We shall not be able to eliminate leprosy until we have a better understanding of its natural reservoir,” says Donoghue. “There are several interesting reports that indicate that there may be an environmental reservoir for M. leprae—perhaps even in the soil in endemic regions.” Healthy human carriers also do exist, says Donoghue, who points out that by using sensitive molecular methods it is possible to detect the DNA from M. leprae in people who showed non-specific skin lesions and who had not been thought to have leprosy. Even after a ten-year MDT programme, more than 5% of healthy individuals in a leprosy-endemic area were positive for M. leprae DNA in their nasal passages, a recent study found, suggesting a high level of environmental contamination. “Before anyone can talk about eliminating the disease we have to understand where the organisms are found, and the circumstances that result in an active infection,” Donoghue says.

Finally, important research issues remain to be addressed. They include developing improved diagnostic tests and better ways to monitor and treat nerve damage, and understanding why MDT has not interrupted transmission. “We shall not be able to eliminate leprosy until we have a better understanding of its natural reservoir,” says Donoghue. “There are several interesting reports that indicate that there may be an environmental reservoir for M. leprae—perhaps even in the soil in endemic regions.” Healthy human carriers also do exist, says Donoghue, who points out that by using sensitive molecular methods it is possible to detect the DNA from M. leprae in people who showed non-specific skin lesions and who had not been thought to have leprosy. Even after a ten-year MDT programme, more than 5% of healthy individuals in a leprosy-endemic area were positive for M. leprae DNA in their nasal passages, a recent study found, suggesting a high level of environmental contamination. “Before anyone can talk about eliminating the disease we have to understand where the organisms are found, and the circumstances that result in an active infection,” Donoghue says.

Another cause for serious concern is that the coalition that stands against leprosy is not as solid as it should be. In 1999, the Global Alliance for the Elimination of Leprosy (GAEL) was formed to inject new energy into the elimination campaign, bringing together WHO, the governments of the major endemic countries, the Japanese Nippon Foundation, the Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development, the Danish Development Cooperation Agency (Danida), and the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP). Quite soon, major contrasts emerged between some of the GAEL partners, namely between WHO and ILEP, who always remained critical of the “elimination”-focussed strategy. The clash was so strong that ILEP was expelled from the alliance at the end of 2001.

Another cause for serious concern is that the coalition that stands against leprosy is not as solid as it should be. In 1999, the Global Alliance for the Elimination of Leprosy (GAEL) was formed to inject new energy into the elimination campaign, bringing together WHO, the governments of the major endemic countries, the Japanese Nippon Foundation, the Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development, the Danish Development Cooperation Agency (Danida), and the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP). Quite soon, major contrasts emerged between some of the GAEL partners, namely between WHO and ILEP, who always remained critical of the “elimination”-focussed strategy. The clash was so strong that ILEP was expelled from the alliance at the end of 2001. A New Strategy for an Uncertain Future

A New Strategy for an Uncertain Future

The World Health Organization (WHO) dubbed the ambitious project “the final push to eliminate leprosy”. The strategy behind the slogan involves expanding MDT services to all health facilities and making leprosy diagnosis available, training health workers to diagnose and treat leprosy, promoting leprosy awareness and encouraging people to seek and continue treatment. However, despite the impressive results obtained so far by the elimination campaign, this is still a work in progress.

The World Health Organization (WHO) dubbed the ambitious project “the final push to eliminate leprosy”. The strategy behind the slogan involves expanding MDT services to all health facilities and making leprosy diagnosis available, training health workers to diagnose and treat leprosy, promoting leprosy awareness and encouraging people to seek and continue treatment. However, despite the impressive results obtained so far by the elimination campaign, this is still a work in progress.  “We shall not be able to eliminate leprosy until we have a better understanding of its natural reservoir.”

“We shall not be able to eliminate leprosy until we have a better understanding of its natural reservoir.”  Leprosy now occurs mainly in resource-poor countries in tropical and warm temperate regions. Contrary to a widely believed myth, nowadays leprosy is a fully curable disease. A multidrug therapy (MDT) based on the combination of the antibiotics dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine was introduced in 1982 after dapsone-resistant strains appeared and spread. MDT proved highly efficacious in killing the bacteria without inducing resistance, although the optimal length of treatment and associated relapse rates are still controversial.

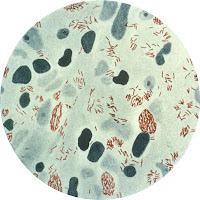

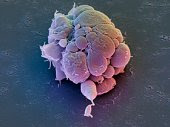

Leprosy now occurs mainly in resource-poor countries in tropical and warm temperate regions. Contrary to a widely believed myth, nowadays leprosy is a fully curable disease. A multidrug therapy (MDT) based on the combination of the antibiotics dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine was introduced in 1982 after dapsone-resistant strains appeared and spread. MDT proved highly efficacious in killing the bacteria without inducing resistance, although the optimal length of treatment and associated relapse rates are still controversial. Recorded diseases, leprosy was also the first human pathogenic condition of bacterial origin for which the causative agent was identified. Despite these historical records, our knowledge of the biology of M. leprae has lagged behind, in good part because it cannot be grown in culture.

Recorded diseases, leprosy was also the first human pathogenic condition of bacterial origin for which the causative agent was identified. Despite these historical records, our knowledge of the biology of M. leprae has lagged behind, in good part because it cannot be grown in culture.